The Sheikh made some great points about religious violence having a tribal, racial, and otherwise sociological basis rather than any sort of profound theological grounding in Islam’s scriptures. The former Muslim in the conversation, now a Christian, was in complete agreement: there are passages that seem to justify violence upon those outside the faith, and others that no more or less vaguely discourage it.

Dr. Al-Hussaini’s observation applies to so many aspects of how we live out our religion: we think we’re basing the way we live on the truth, when so often it’s the other way around. We often say we’re being “biblical” when we find what we’re already conditioned to believe somewhere in the pages of the Bible.

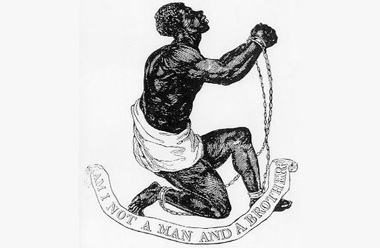

For instance, look for an airtight biblical rationale for our horror at the practice of slavery. You won’t find it. You will find biblical principles such as love for one’s neighbor that some Christians in the last couple of centuries finally recognized as philosophically and theologically opposed to the practice, but there were scads of Christians who had massive blind spots in that area because of their culture’s acceptance of the practice. They even found Scripture that no less explicitly implied the legitimacy of slavery to back them up in much the same way that Muslims living in cultural contexts that have not eschewed racism and tribalism find it easy to find justification for their violence within their holy texts.

For instance, look for an airtight biblical rationale for our horror at the practice of slavery. You won’t find it. You will find biblical principles such as love for one’s neighbor that some Christians in the last couple of centuries finally recognized as philosophically and theologically opposed to the practice, but there were scads of Christians who had massive blind spots in that area because of their culture’s acceptance of the practice. They even found Scripture that no less explicitly implied the legitimacy of slavery to back them up in much the same way that Muslims living in cultural contexts that have not eschewed racism and tribalism find it easy to find justification for their violence within their holy texts.Our culture influences how we interpret the Bible in ways that exacerbate the inerrantist tendency to miss the tempering, nuancing, or even contrasting points of view offered by other biblical authors. The old maxim of “Scripture interprets Scripture” encourages us to trump and even twist what we don’t understand in Scripture in favor of the passages whose meaning seems obvious to us — which in turn is no doubt influenced by our sociological contexts. Somewhat ridiculously, those who do not “allow Scripture to interpret Scripture” by creatively reinterpreting passages that challenge our view to better coordinate with passages that bolster our view are said to have a “low view of Scripture.”

As is clear in the above example of the Bible’s lack of a clear condemnation of slavery, the authors of even the New Testament were not exempt from these cultural blind spots any more than we are. Scripture was created within and influenced by the fallible human cultures of its authors. Taking this into account, it becomes clear that letting Scripture interpret Scripture unfairly subjugates the cultural/sociological perspective of one biblical author to another; whether we like it or not, we must allow culture to interpret Scripture. In order to get any meaning we must consider the culture that created each passage and take necessary steps to compensate for our cultural biases. Even if you believe the Bible is inerrant, you need to take each passage back to the context under which it was inspired in the same way you do when you appeal to progressive revelation as a defense for things like the OT’s embrace of the slave trade.

The convictions of the biblical writers can and, I would argue, should have an influence on our beliefs and ethics. But even the (Muslim) inerrantist Sheikh Dr. Muhammad Al-Hussaini realizes that there is a difference between a scriptural rationale and a scriptural justification for our actions. I do wish more Muslims understood this; even more, I wish more Christians did.