Paul Copan writes:

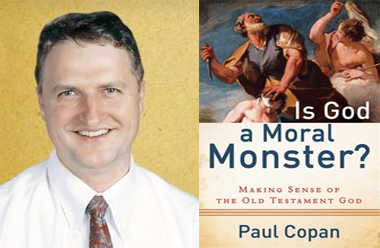

Paul Copan writes:Thom Stark has offered a lengthy response to my book Is God a Moral Monster? His online book is entitled: Is God a Moral Compromiser? When a book is laden with sarcasm, distortions, and ad hominem attacks, genuine dialogue and cordial exchange—the stuff of genuine scholarship—become difficult, if not preempted.

Sarcasm I admit to. Distortions, in a very few places, not at all “laden.” Ad hominem attacks, I disagree. But I acknowledge that much of the tone of my review made it difficult for cordial exchange, and for that I am sorry. I honestly did go through before publishing it and attempted to tone it down, and in more than one place, I made sure to state very clearly that I am not trying to make judgments about Copan as a person, but rather about the quality of his scholarship and of the affects his work has had and will continue to have on Christians at the margins of faith.

My good friend Matt Flannagan, with whom I have collaborated on various projects, has extensively engaged with Stark in the past. (Note: I have posted his response alongside my posting.) I’ve held off on commenting on Stark for this very reason, as the experience of others shows that engaging with Stark on such topics tends to be unproductive.

Actually, I was just beginning to have a productive dialogue with Matt over on his blog, but he seems to have suspended it in order to write his evaluation of my character. I have had countless productive conversations with countless individuals from every ideological perspective. My approach is generally stark when I believe such an approach is called for, but I hope Copan will find that engagement with me can be quite productive. I’ll have more to say about my engagements with Matt in my response to his post.

First, Stark accuses me of ignoring the critical scholars. Keep in mind that I am writing for a popular audience—a group that isn’t going to read at a scholarly level but who are reading the New Atheists. Mentioning these critics is simply a springboard to launch into the topic of Old Testament ethical issues; these men are hardly legitimate sources of critique, even if they raise points discussed by critical scholars.

I find this response unsatisfactory. Not only did Copan fail adequately to respond to the so-called New Atheists (for every five bad arguments they make, they make at least one good one), Copan failed to address the problems with the biblical texts that go much deeper than the so-called New Atheists are equipped to venture. Since Copan by and large ignores the arguments of critical scholars, he has given his popular audience the impression that the problems with the Bible are resolved by responding to the primarily surface-level criticisms of the New Atheists. But I have more respect for popular audiences than that. The question isn’t “What are the problems that most pew-Christians perceive?” The question is, “What are the real problems?” If Copan wishes to genuinely help Christians wrestle with the hard questions, then it is his responsibility to keep them fully informed and to tackle the real issues with them.

Second, it’s disappointing that Stark simply writes off Old Testament scholars who have endorsed my book, calling them “Little Leaguers.” These include Christopher Wright (Ph.D. Cambridge), Gordon Wenham (Ph.D. Cambridge), and Tremper Longman (Ph.D. Yale). They have earned their stripes at leading academic institutions. Stark’s demeaning talk strikes me as disrespectful and unprofessional.

I actually did not at all mean to identify them as Little Leaguers, but looking back at that paragraph, I see that it seems I did in that I stated that Copan was playing in the Little Leagues and that they were Copan’s teammates. That was an metaphorical error on my part, and entirely unintended. I did not mean to demean their scholarship, especially not that of Gordan Wenham. I do have much less respect for Habermas and Moreland than I do for the others. I critiqued Christopher Wright’s work on the conquest in my book, but I recognize, despite the inadequacy of his arguments, that he was really finding his own arguments inadequate himself. At any rate, it wasn’t my intention to call them “Little Leaguers”—that was an unintentional result of a stretched metaphor.

Now, when I stated that Copan is “playing in the Little Leagues,” that was of course, as is clear, a statement about his choice of opposition—the so-called New Atheists. My point was that the arguments Copan has made in his book would not at all stand up against trained critical Bible scholars; he would have to step up his game considerably in that arena. This remains a valid point, and despite the tenor in which I made the point, I hope Copan takes it seriously.

One gets the impression from reading Stark that those who agree with him are the “real” scholars.

Well, this would be a false impression. Let’s take Richard Hess for instance. He is most certainly a real scholar, even though I think that in many cases his otherwise very good scholarship suffers for his commitment to biblical inerrancy. I’m hardly alone in this opinion, although I may be one of the very few with the hubris necessary to publish it online.

Third, Stark assumes I have no background in biblical studies. Not so. I’d imagine that I’ve probably logged the same number formal academic hours (if not more) in biblical/theological studies than Stark—though Stark would no doubt dismiss such training as “Little League.” I have a B.A. in Biblical Studies as well as an M.Div. (Having studied Greek and Hebrew)—in addition to an M.A. in philosophy and a Ph.D. in philosophy (in which I also took courses in theology). I’m also a member of the Society of Biblical Literature, and I have presented at SBL as well as the American Academy of Religion. Furthermore, I am a Fellow of the Institute for Biblical Research.

Well, let’s clarify some things. First, I did not say that Copan has no background in biblical studies. I said that he is not a biblical scholar (p. 172), which remains quite true. Copan is a professional philosopher of religion, and did his doctoral work in that field. Second, if my pointing out that Copan is not a biblical scholar is what he has in mind when he says that I made “ad hominems,” then I contest this. I did not attempt to make an argument that Copan was wrong on any particular point because he is not a biblical scholar. I stated the fact because I think it is important for people to know that this is not Copan’s primary field. I also pointed out that Wright and Hess are “Evangelical” biblical scholars, because for many that is relevant information, and if it’s not, it should be. Being a conservative Evangelical brings with it a set of assumptions that substantially limits the possible range of textual interpretations because of a commitment to the doctrine of inerrancy. I never claimed that any scholar was wrong because they were Evangelical; but it is nevertheless very relevant information. One won’t find non-Christians or non-conservative Jews making many of the arguments made in Copan’s book. Granted, in some places I stated that certain of Copan’s or Hess’s readings are not surprising given their Evangelical commitments, but never did that statement substitute for an argument against the positions themselves.

Fourth, Stark mentions Baruch Halpern as one of his “Major League” scholars. Yet Halpern has actually written an endorsement for one of Tremper Longman’s coauthored books, A Biblical History of Israel: “The most talented trio in the last fifty years to turn their attention to recounting the history of Israel.” William Dever, another big leaguer (of whom Stark might approve) , recommends this same book: “I cannot imagine a more honest, more comprehensive, better documented effort from a conservative perspective.”

This paragraph is written based on the assumption that I meant to identify Longman as a “little leaguer.” I did not, and I apologize again for the unclarity in my metaphor.

Another evangelical archaeologist (whom I cite in connection with the Canaanite question), Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen (Liverpool), has written On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Eerdmans). This hefty book is robustly endorsed by William Hallo (Yale) and Harry Hoffner Jr. (University of Chicago)—leading scholars in this field, whom I also cite in my book.

Kitchen’s book indeed has a lot of very good and valuable information in it. He is a terrific Egyptologist. But there are nevertheless certain key places in On the Reliability of the Old Testament where Kitchen’s Evangelical commitments get the better of him, and this is acknowledged by many critical scholars, who yet respect him, as do I.

So I think a bit greater academic fair-mindedness is warranted rather than demeaning dismissal and condescension.

I respect good work, and I disrespect bad arguments. I respect much of Hess’s work, but have very little respect for his attempts to salvage unsalvageable texts with arguments that hang from very slender reeds.

Or think of the archaeologist/Egyptologist James Hoffmeier (another evangelical), to whom I refer in my book. Baruch Halpern endorses Hoffmeier’s Ancient Israel in Sinai (Oxford University Press): “Hoffmeier furnishes a sophisticated fresh approach to the Biblical Exodus traditions filled with detailed Egyptological background, and utterly indispensable because of its basis in recent, and in many cases as yet unpublished, archaeological data. This is a virtual encyclopedia of the Exodus.”

I never said a word to disrespect Hoffmeier. His book on the Exodus is indeed full of good information; nevertheless, I, along with the vast majority of scholars within the field of archaeology, am not persuaded by his central thesis, in either this book or his previous one. The general consensus in the reviews is that both books provide an abundance of very good research and information, but fail to substantiate their central claims. Hoffmeier tends to skirt key issues, and his tendency to harmonize and imaginatively reconstruct in order to make up for the utter lack of direct evidence for either the Exodus or the Wilderness period (a lack of evidence to which Hoffmeier admirably admits up front) is not sufficient to displace the wealth of disconfirming archaeological evidence that is widely recognized as insurmountable. Hoffmeier is a serious scholar with an apologetic agenda, and both facts show through very well.

On all of these scores, citing endorsements is fine (I like endorsements), but it is really the critical reviews that matter, and for Kitchen and Hoffmeier, as well as for Hess, the consensus in the critical reviews is that each scholar does very fine and important work, provides a wealth of very good information that is very useful to the whole field, but at the same time display apologetic tendencies that manifest in skipping over relevant data, among other things.

I come down very hard on this kind of thing (and I only came down hard on Hess because he was prominently featured in Copan’s book), not generally in response to academic volumes but in response to out and out pulp apologetics books such as the one under consideration in this discussion. I do so not because I think scholars like Copan et al are stupid (I make this clear on several occasions throughout the review), but because of the deleterious effects I see works like Copan’s having on real people in the real world. Copan may or may not be aware of this. My policy is honesty with the material at all costs first, and discussions about how to be faithful in light of the reality second. But books like Copan’s, for every ten Christians whose beliefs they reinforce, there is at least one Christian for whom these kinds of arguments are the straw that broke the camel’s back. Thus, since I assume Copan is secure in his identity and in his intelligence, I hold very little back (although I do hold back some), for the sake of those who are dying to hear somebody actually confront these texts rather than make lame excuses for them. Hess noted that my review was polemical. Indeed, it was, and intentionally so. Polemics are about swinging the pendulum hard in the other direction, and that is what I’ve found many struggling Christians need to experience. See for instance this review which is representative of the majority of feedback I have received from Christians, and is representative of the kind of feedback I was getting from my original blog series which led me to write the book in the first place. Of course, some at the edges of faith will read my book and decide that they no longer wish to be Christian. But in my view when someone moves on from the faith because they feel informed, this is much to be preferred than those who lose their faith because they feel they have been lied to and belittled by transparently biased apologetics. So my response to Copan was indeed polemical, because my intended audience is those Christians on the verge of a mental or spiritual breakdown, and not the academy. If I were writing a review for an academic journal it would have read very differently.

I realize I’m not, in this review, playing by the academic rules, but I have my reasons for this, and I think they were very clear in the preface. So that is that.

Fifth, as to the charge of selectively citing scholars, I would say this: Look no farther than my own endorsers! There are points at which I would disagree with Longman, Wright, and Wenham (and they with me), but I would hardly call this selective. I have tried to weigh and make judgments of a number of scholars on different sides of the debate.

I’m sorry, but this response is wholly inadequate and verges on intellectual dishonesty. You share substantial agreement with Longman, Wright and Wenham, and they with you. Your disagreements are likely negligible at best, but this is neither here nor there. Endorsements are supposed to make people want to buy the book. Obviously each of Copan’s endorsers were earnest. (Not some of the endorsements on the flap of Hess’s Israelite Religions, I probably shouldn’t add.) But anyway, this is an entirely irrelevant response to my demonstration that Copan on more than a few occasions abused scholarly sources in ways that were very misleading to those who don’t know any better. Citing Niditch to support Copan’s claim that the Bible condemns human sacrifice, without telling his readers that Niditch in fact argues the opposite, is dishonest. Copan may want to claim (as others have in his defense) that technically he’s not deceiving his audience because the term “dominant voice” implies another voice that is not dominant, but honestly, how many pew-Christians are going to pick up on that? Of course, this dishonesty was worse in Copan’s online article, where he cited Niditch against Rauser, when in fact Rauser was articulating Niditch’s position. This is dishonest. That is not at all the same thing as an endorser finding good things to say about Copan’s book even though they disagree about some things. Mark Smith’s endorsement of Hess’s book was like damning with faint praise, but it wasn’t dishonest. He meant everything he said, and he was able (rightly) to say some good things about it. They disagree a great deal, obviously, but Smith wasn’t dishonest for endorsing Hess’s book. But to quote Niditch in support of a position that is exactly the opposite of the position she holds is dishonest.

Copan does this sort of thing on a number of occasions (and in my response to Hess I’ve pointed out a case where he does this too, with Mazar). Arguing that such quote-mining is “technically not dishonest” is not honest, because the only people who can recognize that technicality are the ones who know what’s really going on. Everyone else is going to think the critical scholar quoted really does support Copan’s position when in fact they do not. Another example is when Copan says that most scholars see Deuteronomy as later than earlier legal texts in the Pentateuch, but Copan makes this seem as if they’re arguing that Deuteronomy was written, like, last thing before Moses died. Obviously in reality, “most scholars” argue that most of Deuteronomy was written in the seventh century, with a substantial revision in the sixth.

And so on and so forth with the misleading references to scholarship.

What’s more: have I really duped these Cambridge- and Yale-educated scholars so that they endorsed my book without reading it, or are they completely misinformed too?

I can’t answer this last question, but again the term “Evangelical” is probably relevant here. Copan certainly hasn’t duped any critical scholars.

Sixth, consider the question of worldview/philosophical as well as hermeneutical assumptions. For example, one’s presuppositions will affect the degree to which one gives the benefit of the doubt to Scripture’s authors’/editors’ trustworthiness. One’s presuppositions will affect one’s view of the Scripture’s canonical coherence and mutual reinforcement (as Matt Flannagan notes in his post). One’s presuppositions will also affect whether one views Yahweh as a mere tribal deity in Israel’s history (before the fifth century BC) or as the “one true God.”

One of the commenters on Copan’s post has already responded adequately to this old canard. I’ll quote him here:

A short comment on your sixth point about presuppositions: While it is certainly important to recognize one’s starting presuppositions in any field of study, the goal is to make as few and as limited presuppositions as possible. The answer to the question “Does the Hebrew Bible portray YHWH as the one true God?” is not something that has to be presupposed. It can be absolutely addressed by an unprejudiced look at the text. If people see polytheistic syncretism in the text, it is because they see polytheistic syncretism in the text, and they have every reason to expect it given the cultural environment in which the texts in question were produced. Ideally the same if they see the opposite. These things do not have to be presupposed. Is it really giving the authors the “benefit of the doubt” to believe that they are teaching the things you believe? What if they meant to portray YHWH as a member of a pantheon. You are not respecting them by suggesting that they didn’t. . . .

I think that most critical scholars do try to weigh the data carefully though: the more internal evidence from the Hebrew Bible casts doubt upon its reliability, the more damning the lack of archaeological confirmation becomes.

I [am] concerned about the implication that one will see polytheism in the Bible or fail to see it depending on their presuppositions. A critical approach to the Bible does not presuppose that the Bible has polytheistic elements. It simply fails to assume that it does not. Whereas an apologetic approach assumes that the Bible must be monotheistic throughout, and interprets the text accordingly. In this sense, the critical approach is more objective because it has one less burdening presupposition.

This is exactly right. Mike B. makes two points that I’ve made repeatedly: (1) Inerrancy is a hermeneutically limiting presupposition. (2) If an author of a biblical text did mean to say something that orthodoxy does not permit, then it is disrespectful to that biblical text to try to conform it to orthodoxy. I refer the reader to the first three chapters of The Human Faces of God for an extended discussion of these, and other, important points about why inerrancy devalues Scripture.

As for Copan’s reference to Matt Flannagan’s repeated charge that I don’t understand canonical hermeneutics, I’ll refer the reader to my discussion of canonical hermeneutics in the ninth chapter of Human Faces. Of course, it’s important to note that the practice of canonical hermeneutics does not at all necessitate a commitment to biblical inerrancy. Childs, after all, was no inerrantist. I was beginning to have a polite discussion with Matt about this on his blog, but he seems to have gotten busy writing other things. Hopefully we can pick it up again soon.

Take the last set of dueling assumptions. When we see that Yahweh is the “cloud-rider” on a chariot (2 Sam. 22:10-12; Psalm 29; 104:3; Isa. 19:1), is this syncretistic? After all, in Ugaritic literature, Baal is the chariot rider on the clouds. What of the mentions of the Chaoskampf (the divine effort to subdue chaos and bring order) in the Bible? There’s Yahweh’s battle against Leviathan the dragon (tanniyn) mentioned in Isa. 27:1; yet the Ugaritic refers to Baal’s fighting against tannin (dragon) and lotan. Is this polytheistic syncretism? I would argue that the biblical texts are polemical and subversive. They appropriate literature familiar to ancient Near Easterners, and they present Baal and other deities with the one true God, Yahweh. Yahweh literarily displaces them.

Of course this is what Copan would argue. I have no comment.

The same is true in the creation story: the deep, the darkness, the sea, and even the heavenly bodies were gods in their own right in ancient Near Eastern cosmogonies (accounts of the world’s origin). Yet in Genesis 1 they are domesticated and seen as the creation of God himself. Again, we have displacement, not polytheistic syncretism.

Well, let’s not discuss the consensus of critical scholarship which dates Genesis 1 to Israel’s post-polytheistic period.

Another presuppositional issue is that the place of archaeological discovery and what this may “prove” or “disprove” about the Bible. For example, he claims that I offer no evidence for the exodus or the Canaanite conquest.

I don’t remember claiming this, but I’ll be happy to be shown where. My memory of what I wrote is that Copan has distorted the archaeological evidence.

For one thing, this wasn’t my purpose in writing the book, even indirectly.

I haven’t nor am I claiming it should have been. I merely objected to Copan’s misunderstanding or misrepresentation of the data. For instance, he claims that it is not surprising that Israelites and Canaanites had virtually indistinguishable material culture because both peoples were heavily influenced by the Egyptians. In fact, the record shows the opposite. They do have identical material cultures, but it does not reflect Egyptian influence.

For another, I cite books that address these topics at length—namely, those authored by James Hoffmeier and Kenneth Kitchen. For a brief overview, however, see “Did the Exodus Never Happen?”. Along these lines, one could also examine Tremper Longman’s coauthored A Biblical History of Israel (Westminster John Knox Press). No, the evidence—which is indirect—does not prove or disprove the exodus. Rather, it presents plausible historical context for the event’s historical occurrence.

Yes, other factors disprove the biblical portrait of a mass-exodus, as I discuss in the review and as Copan does not discuss here.

In addition, I do mention in the book the archaeological evidence surrounding the gradual transition from Canaanite domination to Israelite domination. I follow Egyptologist Alan Millard’s work. He argues that Israel’s settling in the land was a gradual infiltration rather than a dramatic military conquest, which is what the biblical text affirms.

Again, see my remarks on this model in the review, to which Copan has not responded.

Seventh, as I’m in the midst of a number of writing and editing projects, I’m even less inclined to respond to Stark, at least with any comprehensiveness.

This is understandable but unfortunate, especially for all those who were persuaded by my review yet who really wanted to be persuaded by Copan.

Even before Stark wrote a response, I had begun compiling material based on further research as well as cordial (!) interaction various friends and critics who offered helpful suggestions. For instance, I should have elaborated more on the word(s) herem/haram (sometimes translated “utter destruction/utterly destroy”) at places like Jeremiah 25:9, where Yahweh promises to “utterly destroy” Judah by using Babylon. Were the majority of Judahites annihilated or destroyed as a people?

Prophetic judgment literature constantly vacillates between threat of destruction and promise of redemption. But I’m not sure Copan really wants to open up a discussion about all the failed prophecies in the Bible.

Eighth, I have approached Baker Books about a second edition in which I could incorporate this further research and also do some tweaking/clarifying on some certain points Stark raises.

I’m glad to hear this. I sincerely hope that the “tweaking/clarifying” is fairly substantial. I look forward to reading it.

Also, I am working on coediting a book on warfare in the Old Testament (IVP Academic). Matt Flannagan and I have written a lengthy chapter that responds to the sorts of challenges Stark raises on the warfare issue. Also, I’ll be presenting at a conference in November on slavery in the Old Testament. This will be an occasion to reply to any relevant challenges that Stark raises. So stay tuned.

Well, I’m not sure what “relevant challenges” I am able to raise, since Copan’s “response” didn’t even scratch the surface of the substance of my review or engage directly about 99.99% of the criticisms I made. Nevertheless, I look forward to reading and responding to Copan’s and Matt’s new chapter on “the warfare issue,” and I also look forward to hearing (somehow) what Copan will have to say on slavery. I’m not sure if Copan intends to put his conference paper up online, but at least with regard to the warfare chapter, it’s unfortunate that Copan’s response to the lengthiest portion of my free review won’t be up online. Hey, regardless, I’m glad it’s coming.

Finally, Stark’s critique resorts to much bluster, condescension, and distortion; he makes abundant claims and arguments that are either false or tenuous (as Flannagan points out).

Well, Matt doesn't at all engage the review or speak to any specifics, and the truth is he misrepresented me as often as I misrepresented him, but as far as I'm concerned that's part of the fun of the discussion. (Not to imply that my misunderstandings of Matt's position were ever intentional; they were not.)

As a specific sampling, Old Testament scholar Richard Hess (whom I cite frequently in my Moral Monster book and who also endorsed it) responds to Thom Stark in a separate post at Parchment and Pen.

Hess corrected me on a few points, which I’m glad to be correct on, but each of which really had no real bearing on the primary arguments. Other than the few points of correction, I found Hess’s response to be unsatisfactory.

In conclusion, I’d like to thank Copan for coordinating this triune reply to my review, which I think will benefit a number of readers. I wish Copan had more substantive things to say in response, but I suppose that’s what I get for not abiding by all of the unwritten rules of academic etiquette. Copan has focused primarily on this fact, which no doubt will make those who already agree with him very happy. I’m of course more concerned with those in between, who are trying to figure out how to go on. For me this was never about myself and Copan, but I certainly understand Copan’s disinclination to debate ancient texts with an asshole. I’d rather watch X-Files myself.