In the Gospel of Luke’s last supper narrative, Jesus says the words of institution and immediately, the disciples break into an argument about who is the greatest. It should not surprise us, therefore, that this has often been the modus operandi of the Church ever since. Who is the greatest? Who may come to the table? Who may preside at the table? What is it, exactly, that happens at the table? Is it my metaphysical scheme or yours? Is Christ Really present, or is this a simple remembering? The Eucharistic meal, after which Christ tells his disciples that the least is the greatest, and then proves this by being killed by the powers-that-be, has become a show of, or a grasping at, power. Rather than recapitulating in the Eucharist the subversive final meal of Christ as hospitality and forgiveness—as justice—the Real Presence exploits the powerlessness of Christ at his death to serve the power of the Church which exhaustively contains or grasps at the Real.

In the Gospel of Luke’s last supper narrative, Jesus says the words of institution and immediately, the disciples break into an argument about who is the greatest. It should not surprise us, therefore, that this has often been the modus operandi of the Church ever since. Who is the greatest? Who may come to the table? Who may preside at the table? What is it, exactly, that happens at the table? Is it my metaphysical scheme or yours? Is Christ Really present, or is this a simple remembering? The Eucharistic meal, after which Christ tells his disciples that the least is the greatest, and then proves this by being killed by the powers-that-be, has become a show of, or a grasping at, power. Rather than recapitulating in the Eucharist the subversive final meal of Christ as hospitality and forgiveness—as justice—the Real Presence exploits the powerlessness of Christ at his death to serve the power of the Church which exhaustively contains or grasps at the Real.The term “hyperreal”1 has been used by different theorists with multiple facets and emphases. Jean Baudrillard’s use of “hyperreal” describes the convergence of fact and fiction, where fiction rules out. He defines it as “the generation by models of a real without origin or reality.” The sign becomes the signified. The simulacrum becomes the real. As one eminent professor put it, “grape popsicles don't taste like any real grapes, but we don't want them to. Or . . . food in Mexico (the real) doesn't taste like Taco Bell (the hyperreal), and this is disappointing to tourists.”2 So it is in this sense that I want to look at the traditional transubstantiation of the elements of the Eucharist and also the Real remembrance of Christ at communion as not-really Real, but hyperreal in a Baudrillardian sense.

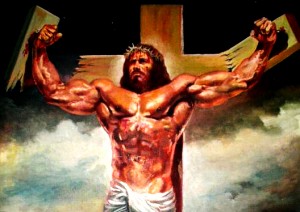

The weakness of Christ is transmuted to the power of the Church. The powerful soteriological Christ simulated by the Church militant replaces the canonical Christ, who identifies with the oppressed. By bringing forth the hyperreal Christ, the Church grasps at power. The priest manufactures, or conjures the hyperreal Christ, which is endlessly reproduced and consumed. Christ must go through the proper channels, must make his way down the corporate ladder to the consumer. We have produced and reproduced Christ in our image. Christ comes (or is remembered) only in this way, to these people, in this metaphysical scheme. The powerful Christ is a fiction which is substituted for the real Christ, who did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, who never chose power, who was found among the weakest, and the least. The power-brokers and apologists armed with their Real Presence, or their Real remembering, march forward toward victory trampling all those who have been taught not to recognize the obviously real Christ they possess.

In order to counter this hyperreal presence of transubstantiation which elides the kenosis of Christ, and therefore the event of justice, we may turn to Derrida’s use of the hyper-real. For Derrida, the Real always eludes our language. The hyper-real is that which is the reality just beyond our grasp—as Caputo puts it. When we think we grasp the Real, it slips away. Even if the doctrine of transubstantiation is true, when we grasp the elements, we do not feel or taste the Real, we feel wafer or bread, and taste wine. The Real Presence of Christ turns out to be just beyond our senses, just beyond (ὑπέρ) the Real. A hyper-real presence recognizes the sense of mystery about what is happening at the Eucharist. As my priest once put it, “Jesus took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to his disciples, saying, ‘Take it; this is my body,’ and they did not know what he was saying.” This mystery keeps the Real just beyond our understanding. We enact Christ’s praxis, loving the unlovable, standing up to power with forgiveness. There is no power to be gained at Christ’s hyper-real coming.

At the Eucharist, we call out (epiclesis) for the spirit of God, the spirit of justice, the event, to come. Give us this day. Christ is hyper-really present; “This is my body,” turns out to mean the gathered community enacting the mission of Christ to the outcast, to the least of these. The event of justice is brought near; the kingdom has come, though as Derrida would remind us, it is always just beyond (or in more traditional theological terms, now and not yet). It is beyond, not-yet, because there are still those that we have excluded, there are still those who come to the feast and go away empty.3 This hyper-real presence opens up the possibility of endless interpretation—which for Derrida is the possibility of justice—of endless deference to the other, rather than a grasping at a powerful hyperreal Jesus.

This is not meant to be a critique of a certain metaphysical scheme.4 It is not a polemic about memorial symbol vs. real presence. And it is not an argument against church hierarchy. My aim is to open up a way to talk about the inauguration of the kingdom that takes place at the Eucharist in a way that transforms our conversations about these issues. The hyper-real presence of Christ is a presence and a memorial, a remembering, a re-membering,5 and a re-remembering. It also opens up a way to reimagine the hierarchy. In the calling of the Spirit to come and the hyper-reality of Christ, the church enacts a perichoretic act of kenosis: Each other deferring to another other. There is no absolutely Real Presence with which to gain metaphysical power. Your and my interpretation is a gift given, rather than a dogma laid down. As the church enacts the Trinity, the hierarchy gets flipped upside down. The bishops’ miters fall off as they bow in deference to the laity. This is not necessarily a prohibition on hierarchy, but it is a Christian subversion of it. She who is greatest is she who is the servant of all. A bishop or priest in Christ’s church is nothing like a king, or emperor, nothing like a president or CEO of a corporation—no matter how many times the church has capitulated to the obtaining of power.

The gathered community embodies Christ at his hyper-real coming in the Eucharist. Here all are fed, including the shut-ins, and those who are shut out. The grace manifested in the sacrament of the Eucharist is freely given. The universal Christ is manifested in the universal giving of grace by means of the grace-filled gathered community. Christ becomes hyper-really present in the gathered community and then freely, publicly, and communally given to the world. As Bishop Frank Weston put it, “it is folly—it is madness—to suppose that you can worship Jesus in the Sacraments and Jesus on the Throne of glory, when you are sweating him in the souls and bodies of his children. It cannot be done . . . Now go out into the highways and hedges where not even the Bishops will try to hinder you. Go out and look for Jesus in the ragged, in the naked, in the oppressed and sweated, in those who have lost hope, in those who are struggling to make good. Look for Jesus. And when you see him, gird yourselves with his towel and try to wash their feet.” 6

- Since in this post I contradistinguish two forms of the hyper(-)real, I will use “hyperreal” when using it in a Baudrillardian sense, and “hyper-real” when dealing with it in the Derridean sense. For Baudrillard’s usage see Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations. For an explanation of Derrida’s usage see John D. Caputo, For the Love of Things Themselves. [↩]

- I owe much of the Baudrillardian insight, as well as this quote, to Ted Troxell [↩]

- 1 Cor. 11:20ff. [↩]

- though perhaps a critique of all metaphysical schemes [↩]

- 1 Corinthians 12:12 -20 [↩]

- Bishop Frank Weston, Our Present Duty. [↩]